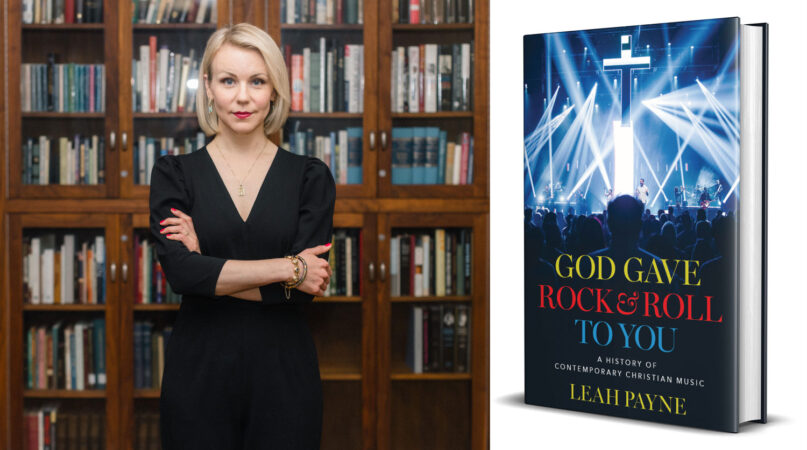

God gave rock ’n’ roll to everyone, as the British rock band Argent once sang. And everyone includes the religious-right powerhouse James Dobson, as well as the legendary rock band Kiss, both of whom tried to reach the souls of teenagers through the power of rock ‘n’ roll. Both Kiss and Dobson get a mention in “God Gave Rock & Roll to You,” a new history of the cultural power of contemporary Christian music from religious historian Leah Payne. The book traces the rise of CCM, which Payne describes as “part business, part devotional activity, part religious instruction,” from its humble beginnings to its 1990s heyday — when Amy Grant’s “Baby Baby” was a monster hit — and then to the current dominance of a handful of megachurches.

She also looks at how Christian leaders like Dobson, Billy Graham and concerned evangelical moms known as “Beckys” sought to harness the power of rock music to keep their kids Christian and to shape the broader culture. “The story of CCM is the story of how white evangelicals looked to the marketplace for signs of God’s work in the world,” she writes. Payne draws on interviews with artists, fans and record executives as well as her own training as a religious historian to trace the rise and fall of CCM. The book is filled with sharp insights and small details about the role that Pentecostalism and Nazarene holiness codes played in shaping Christian music for decades. Rather than being built on generic evangelical beliefs, she argues, Christian music was influenced by both the ecstasy and the strict boundaries of those traditions.

Early on, Payne details how Pentecostalism inspired “Great Balls of Fire,” an early rock ‘n’ roll hit by Jerry Lee Lewis, cousin to televangelist Jimmy Swaggart. That term was used by Southern Pentecostals to talk about the Holy Spirit — a reference to the Book of Acts, where the spirit descends on early Christians in the form of fire. For Pentecostals, being filled with the spirit often comes with a sense of euphoria, often displayed through singing. Rockers like Lewis took advantage of that connection, said Payne. “You can imagine how scandalizing it would be for Pentecostals when Jerry Lee Lewis uses that expression as a very thinly veiled reference to sex,” said Payne in a recent interview. “They felt that it was desecrating their holy practices.”

Payne said the purity codes of groups like the Nazarenes also played a role in Christian music, which was seen as a more wholesome version of rock music. Leaders like James Dobson, who grew up in the Church of the Nazarene — a holiness tradition — used music to spread ideas about chastity and modesty for women. “Women who were holiness preachers were super modest, but that made them spiritual bosses,” said Payne. “They were out there exorcising demons and telling men what to do from the pulpit.”. Folks like Dobson, Payne argues, kept the modesty part of holiness codes, but they domesticated it — spreading the idea that women should be submissive at home rather than powerful.

But women also played a major role in shaping Christian music. The genre’s biggest stars were women — like Grant — and women were its biggest customers. Especially a woman known as “Becky” — an industry term for the suburban evangelical moms who bought the majority of Christian music. The name “Becky,” said Payne, was used by marketing executives and record producers to determine what songs got recorded and often determined which artists became stars. Payne points to the example of Carmelo Domenic Licciardello — better known as Carman—who became a star in the 1990s. She said record company executives were not big fans of Carman, whom she described as a Christian version of Liberace.